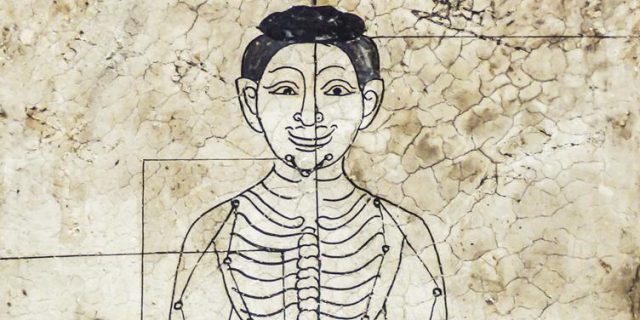

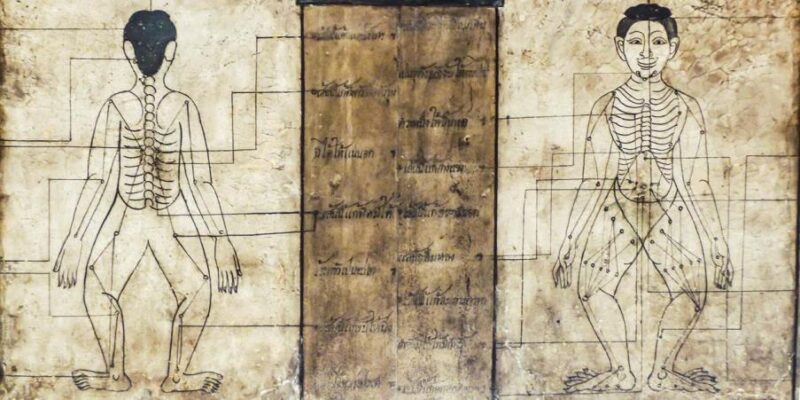

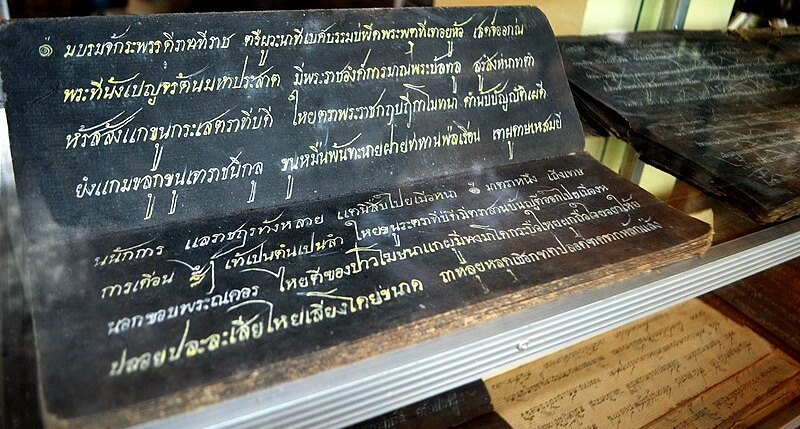

Apart from the Rue-si Dat Ton statues that are placed in the Wat Pho temple garden, the Samut Thai Khao manuscript (also called the Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Dam or Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Khoi) is one of the oldest evidences of the existence of Reusi Datton knowledge in ancient times.

The Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Khao (also written Samut Thai Kao) is an ancient manuscript (a folding-book with black pages) dating from 1838, and contains 80 Reusi Datton drawings i.e. illustrations, similar to the 80 statues in the Wat Po temple garden. Each illustration is accompanied with a poem i.e. description of the Yogic pose or technique performed. The official name attached to it is: The Book of Eighty Rishis Performing Posture Exercises to Cure Various Ailments.

Yet, before we further explore the contents of this Reusi Dat Ton manuscript itself, first something about the terminology used with respect to the ancient Thai folding books. Typically, in Thailand, these types of books were called Samut Khoi or Samut Thai, and were used in various Buddhist cultures, like in Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

The Thai word “Samut” means “notebook,” “book,” or “booklet.” The word “Khoi” (or “Koi”) stems from the Khoi tree of which the paper of the books was made. Then we have the difference between the words “Khao” (or “Kao”) meaning “white,” and “Dam” meaning “black.” As such, “Samut Thai Dam” and “Samut Thai Khao,” respectively mean “Thai Black Book” and “Thai White Book.”

Now, the Reusi Dat Ton manuscript we talk about in this post (see the lead image of this post) would more accurately be called the Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Dam and not Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Khao, because it’s drawn on charcoal blackened paper. Nevertheless, you will find that many in the Reusi Dat Ton community would use both names to refer to this particular manuscript, because you can indeed also find the white version of this folding book (Rue-Si Datton Samut Thai Khao) in the National Library in Bangkok.

In any case, let’s go back to the Reusi Dat Ton manuscript. Mind that the 80 line drawings in the Samut Thai Khao are only a selection of all known Reusi Dat Ton techniques, which some say to be at least 127 (as it is, there’s also a book of 127 postures to be found in Bangkok’s National Library), although others extend this number to 200 to 300 techniques and poses.

The accompanying poems with each drawing were written by the Thai King Rama III and a variety of other people, such as monks, noblemen, important officials, artists, including common people. The result of that effort is that today many doubt the complete accuracy of those descriptions (poems) in relation to the Yogic stretching or massage techniques being depicted.

Moreover, in the well-known Wat Pho Thai Traditional Medical School “The Book of Medicine” of 1958, a range of Samut Thai Khao poems is (freely) copied, sometimes accompanied with Reusi Dat Ton poses that don’t match the description, adding to the general confusion.

Yet, in spite of the inaccuracies, the Samut Thai Khao of Rue-si Dat Ton is an important document, not only artistically, but also as historical evidence of the role Reusi Dat Ton played (and still plays) in Thai society. The manuscript is conserved in the Thai National Library in Bangkok. One needs special permission and an appointment to see and/or browse the book.