Although it’s not a secret at all, it remains fairly unknown that Yoga consists of four classic paths: Jnana Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Karma Yoga, and Raja Yoga. In the West, we usually tend to focus primarily on “physical” Yoga aka Yoga as Exercise, that is, Raja Yoga, and it’s often assumed that Raja Yoga equals Yoga.

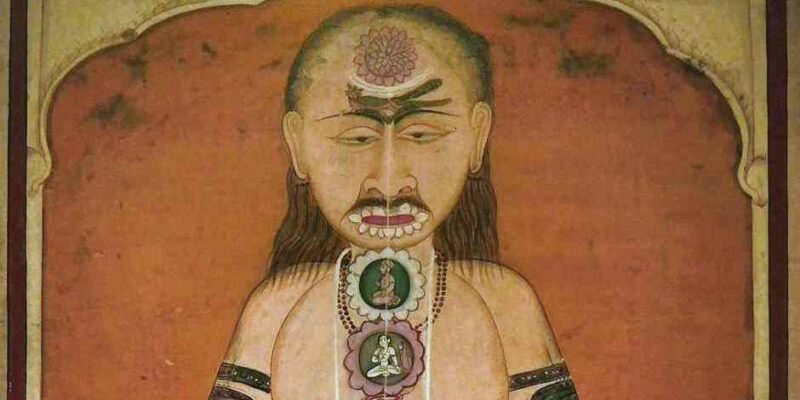

To dive deeply into the differences between the various types of Yoga is a whole other subject, but what we nowadays call Ashtanga Yoga, Kriya Yoga, Hatha Yoga, Pranayama Yoga, Vinyasa Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, Iyengar Yoga, Bikram Yoga, and the like, are mainly derivatives from Raja Yoga as revealed by Patanjali in the famous text Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Now, the goal of Raja Yoga is to come to a certain cultivation of the mind using meditation techniques, and through meditation achieve Spiritual Liberation i.e. Spiritual Enlightenment. But in order to be able to meditate, that is, to come to a concentrated and afterwards meditative state, an extensive range of Asanas (Yogic postures) and Pranayama (breathing exercises) need to be practiced. (For the sake of briefness, I’ll skip what meditation is, or is supposed to be.)

Over the years, we have bundled these Asanas and Pranayamas in a variety of Yoga styles and modalities. And these are the postures and breathing techniques we also find in Thai Massage. It’s because of this aspect that Thai Massage is also known as Thai Yoga Massage, “Passive Yoga” or “Yoga-For-Lazy-People.”

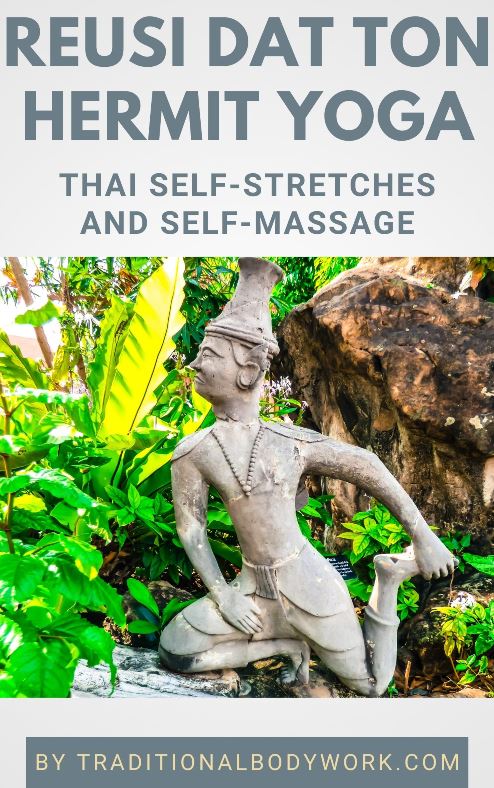

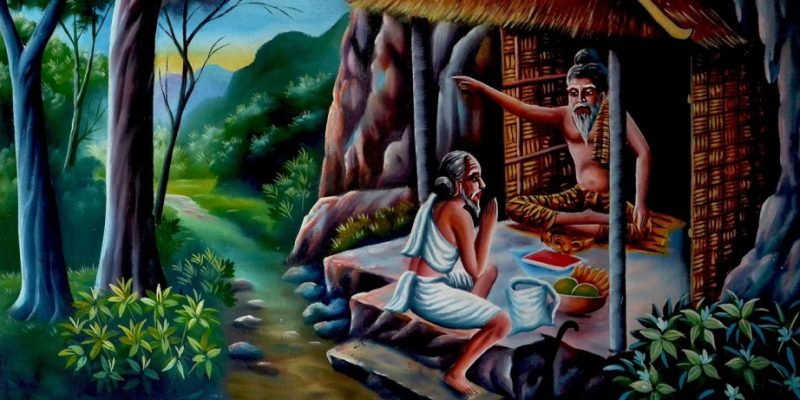

The history of Thai Massage shows its origin emerging in India. Healing methods, mental, and physical exercises spread together with Buddhism through the rest of the Asian continent and a very specific integration of “healing touch” gradually developed, ending up in its current form in Thailand. As it is, Thai Massage is most likely initially influenced and formed by Ayurvedic concepts and Yoga philosophy, and later on by various conceptual and practical contributions from healers originating from Nepal, China, Tibet, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and of course … from Thailand.

It’s for an important part the smooth transitions into Yoga postures (Asanas) that give Thai Massage its attractive gracefulness. It’s this magnificent blend of classic massage, harmonics, Yoga poses and acupressure, executed through seamless transitions, which probably makes Thai Massage the most complete, most versatile bodywork.

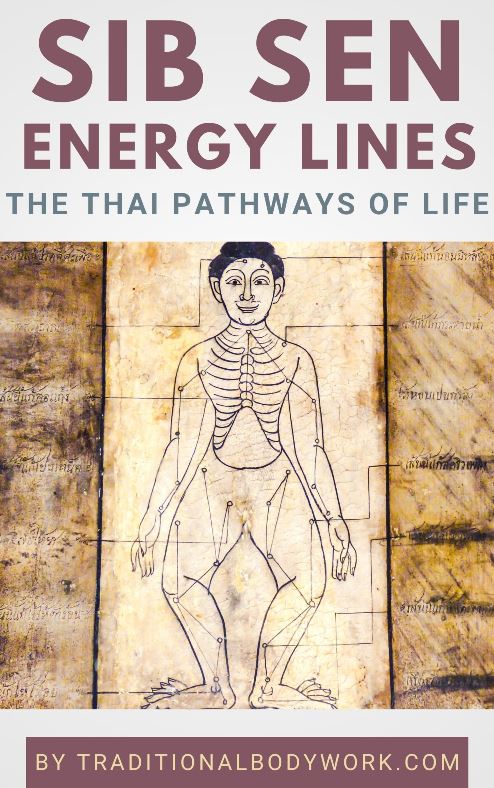

But it’s of course not for the beauty of postures we use Yoga poses in Thai Massage. The philosophy is the same as in Yoga. We try to “open-up.” Open up the Sip Sen Energy Lines, stretching the Energy Lines, stretching muscles, tendons — bodily tissue. We use Yoga Asanas to increase flexibility, increase range-of-motion, to open up tissue to stimulate our blood supply and thereby promote an improved nutritional and immune system, and overall increased healing performance.

The parallels with Yoga are obvious. Some of the Thai Massage Sen Lines even have the same names as the Yoga Nadis (Indian Yoga Energy Channels i.e. Prana Channels) and are described running almost equally across our body.

The difference with practicing Yoga is that it’s the Thai Massage practitioner who places or puts the receiver in Yoga postures. And doing so we can go deeper, we help the receiver to open-up more, stretch more. The receiver doesn’t need the effort from other parts of their body to perform a certain Asana. That’s why Thai Massage is called “Passive Yoga” or “Yoga-For-Lazy-People,” meaning no-effort, no-extra, just experience, letting go, and receive.

Thai Massage receivers who are used doing Yoga confirm feeling “like-having-done-Yoga” after a massage session. But then without the effort. Yoga without sweating. Without watching the Yoga teacher and without doing a posture right or wrong.

Thai Massage and Yoga are basically two sides of the same coin, but with Thai Massage one is able to share deeply together. Two souls mirroring each other simultaneously, exposing each other strengths and weaknesses — without judgment, without holding back. Just opening-up and starting to heal, and to make whole again.