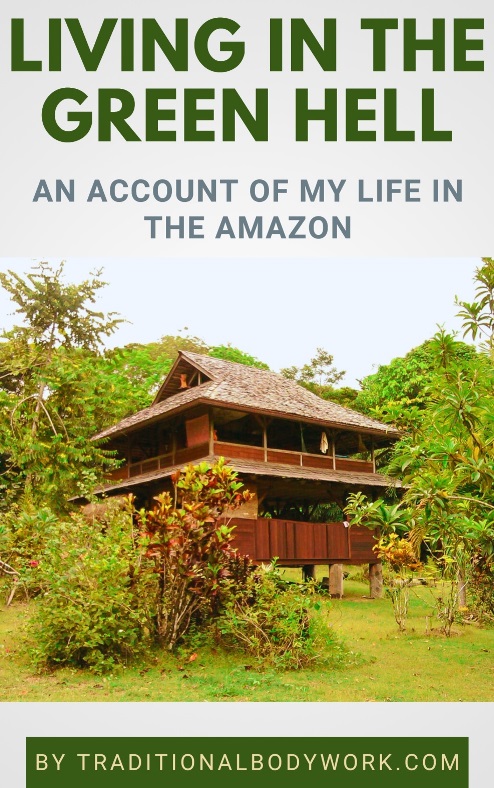

Off-grid daily life in the Amazon Rainforest is downright tiring. It’s perhaps the best way to put it. First of all, it’s very tiring if you want to “do things.” And, unfortunately, you must do a lot of things to keep yourself and your surroundings safe.

For instance, you need to regularly cut the grass and trim the plants around your hut, keep the trees and the forest in your immediate environment in check, cleanse and perform daily checks on insect invasions in your dwelling, such as termites, ants, wasps, and bumblebees, which can ravage the wood of your hut and your roof if you don’t.

That all costs a lot of time, because you need to do these things almost daily due to vegetation that grows superfast in the Amazon, and because of the dazzling number and variety of living species co-existing near you. Apart from time, it also costs a lot of energy because the heat just wears you down.

In addition, when you walk around or sit in the hut, do stuff outside, or in the forest, you always need to be alert on different sorts of animals that can hurt you or your belongings. I’m talking about various types of flies, ants, wasps, bees, spiders, scorpions, bats, centipedes, mosquitos, and snakes, to give some examples.

The way you need to handle your clothing is another tiresome issue. You always need to check on uninvited guests in your socks, shoes, boots, pants, and t-shirts, for instance. One of the tricks to make things safer, is to always turn your clothes inside out, which means that you can already see the inside when you plan to put them on.

So, before wearing your clothes (which are hung or put away inside out), you would shake them, then you would turn them outside in (that is to the right way of how you’d wear them), shake again, and check. In addition, you would tap your shoes or boots in an upside down manner, to make “things” drop out if they would have made “a shelter” inside.

Believe me that it’s all really necessary to do so, and I couldn’t tell you the number of times I’ve found frogs, toads, lizards, ants, weird “unknown” insects, and even snakes inhabiting my clothing.

Now, although you become used to being in a state of continuous awareness or alertness, it’s still very tiring. At times, you just want some godd*mn peace and be able to truly relax.

In the Amazonian jungle, there’s quite a strict daily rhythm because of its location around the equator. It means that it always gets light between five and six in the morning and always gets dark between six and seven in the evening.

You can do your chores until about 10:00 in the morning and then again after 16:00. In the time between, it’s too hot to do things. You would typically rest, or prepare food, and such, or go into the forest where it’s usually pleasantly cool (about 18°C in the morning and 23°C on the day in the area I lived in) because of the dense canopy.

So, between 10:00 and 16:00, I would often go for a hike in the forest, or go to one of the creeks nearby to swim, or combine both. By the way, I would always take a nap from 13:00 to 14:00, which is the hottest time of the day.

Sleeping is always done by being covered with a mosquito net. You want to avoid things like mosquito bites and catching malaria or being bitten by a venomous spider or snake.

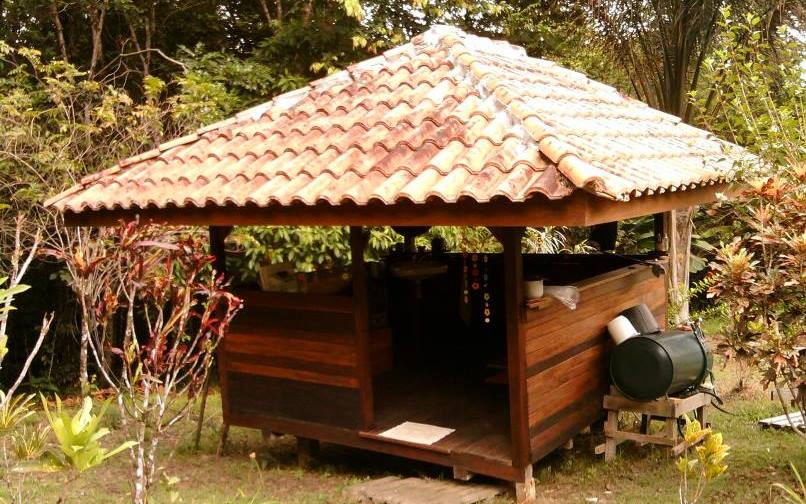

Urinating was done outside, in or near the forest at a spot of our choosing. We used a simple bucket system with sawdust for defecation (a kind of dry toilet system), which needed to be cleaned every day: about 150 meters from the hut in the forest we had created an area to dispose of our feces and cover them with leaves.

Our water supply was arranged by using rainwater, which we collected from the roof into a tank that could contain 1,500 liters. That works fine for showering, washing your clothes, and doing the dishes, except for in the dry season.

The duration of the dry season is about three to four months (roughly from mid-August to mid-December) and then it rains very little, maybe two or three times during the whole period. Nevertheless, when it rains, it’s typically a lot, and then you can refill your water tank. But, in general, it’s not enough to cover the whole season, and you will need to save on your water use.

Luckily, we had a creek about a kilometer from our hut (actually, in the Guianas you have creeks and rivers everywhere close by), so at the peak of the dry season we would bathe there, instead of using our precious water tank supply.

Of course, when you go for a swim in creeks or rivers in Amazonian waters, you always have some risks you need to be aware of, like parasites, submerged obstacles (typically branches and trunks), stingrays, electric eels, piranhas, or certain caimans. Yet, in our nearby creek you’d only find some electric eels, but they usually swim away when they hear you splashing around. There were also some caimans (a type of alligator), but the harmless type that doesn’t bother you.

One of the beautiful things of living in the Amazonian forest is the close contact you have with wildlife. Well, at least, I liked it very much. Now, I’m not talking about insects and such, but about many different types of monkeys, rodents, birds (parrots, toucans, and whatnot), and turtles, large monitor lizards, armadillos, peccaries (wild pigs), huge toads, giant anteaters, caimans, boas (such as anacondas), wild bush dogs, coatis (a type of raccoon), and large spiders (such as tarantulas), to name a few.

Around our hut, you could typically spot various types of wildlife during sunrise and sunset, or on very specific times on the day. For instance, there was always a group of about twenty Saimiris (squirrel monkeys) that would pass the hut (along the canopy) around eleven in the morning or a large monitor lizard roaming the terrain around one in the afternoon. Like us, they have their habits, so to say.

Another particularity is nighttime. It’s actually the loudest period in the jungle. Strangely enough, in the daytime the forest is relatively quiet. It’s basically too hot to go about doing things, not only for us humans, but also for the animals.

Yet, when the sun sets and the night really falls, the jungle comes alive. Trillions of insects start to make their sounds, and the many night animals begin roaming around looking for food. It’s the moment you want to go to sleep, and normally the time you’d want peace and quiet, so it’s definitely something you need to get used to.

In fact, you do get used to it, and it even becomes a kind of lullaby that supports you falling asleep. Then again, when you first come to live in the forest, it’s all very disturbing and somewhat scary. I can remember that it took me about two weeks to get accustomed to it.

However, it was not uncommon to have some night “visitors,” particularly as we slept in an open-air hut without doors or windows, which included bats, tarantulas, and opossums roaming around inside the hut. Especially the opossums make quite some noise when they “inspect” your belongings looking for food, and sometimes you just needed to get up in the middle of the night to “kick them out.”

As for our food, we didn’t rely on the forest. We didn’t plant or something. However, near our hut and on the terrain of the community, there were many types of fruit trees giving mangos, soursops, hog plums, guavas, lemons, and oranges, and in addition, we harvested the various types of palm tree fruits, which you can boil, and usually have a similar structure as boiled potatoes.

Surely you can plant, for instance tomatoes, red potatoes, or lettuce, etcetera, but that means a lot of surveillance and protection because of the insects, rodents, bats, and opossums. It’s a hell of a work. Things grow extremely fast in the Amazon, but at the same time, there are many “hazards” that can quickly ravage your produce.

So, once a week we would go to Cayenne (French Guiana’s capital city), and sometimes we’d visit small town markets to do our groceries. We would buy things like rice, potatoes, pasta, vegetables, cheese, various types of fruits, and such, apart from other necessaries like cosmetics.

We had a car, which we could reach after a half an hour walk through the forest. The car was parked near the dirt road at the community entrance, which would lead to a paved main road going up to the village of Macouria, and then via the main highway to Cayenne (a total of about forty kilometers of trajectory). Sometimes, we would skip a week, but in practice, we went weekly.

The city is about five to ten degrees Celsius warmer than the forest, so that’s something you really notice, and it’s just uncomfortable. In Cayenne, it can easily reach 35°C in uncovered space, while it’s rather between 25°C and 30°C, and cooler in the forest and rural areas.

Anyway, carrying the groceries was quite a hassle because we couldn’t reach the hut by car. We solved this by going with two empty wheelbarrows to the entrance (where the car was parked) and on our return from the city we would fill the wheelbarrows with our groceries to then walk about half an hour along the trails to the hut.

All in all, living in the jungle boasts a very particular type of daily life that asks for a good amount of energy and alertness, while often spending much more time on tasks and chores than you would in a house or apartment in the city.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.