Every now and then I come across columns and essays that have “being Surinamese” and “feeling Surinamese” as their subject, but often I find the elaborations slightly unsatisfactory. Not so much because of factual errors, but rather because the contributions are not complete, that is, they only cover parts of the topic.

I also often find them somewhat uncritical and cautious, and it seems to me that certain items are deliberately left out of consideration, or are a bit obscured. I don’t know exactly why that is; maybe it has something to do with the sensitivity of the theme, or maybe it’s because the Surinamese community (on both sides of the ocean) is not deeply interested anymore.

And admittedly, it is a difficult, pushy subject, extremely multifaceted, and one really has to “sit down for it” if one wants to write a piece that is in any way coherent. And even then one will not be able to be complete, nor without mistakes, or now and again offend this or that person.

Anyway, since “being Surinamese” (or not being it) concerns me personally, I have decided to join “the ranks of the great” and make an attempt (in a completely unscientific way, by the way) to create clarity about this confusing issue. Not only for myself, but also for others who are in doubt. I realize that I’m treading on thin ice here, but on the other hand I’m not afraid to “slip,” so to say, and fall “… on my snout.” It’s of course not my intention to offer you a “table” or “quiz” from which you can deduct whether you are (still) Surinamese, feel Surinamese, or should (still) feel one. That would be very erudite, but downright ridiculous. On the other hand, I will conscientiously try to highlight all relevant factors and perspectives, and provide “healthy and inspiring” comments.

Now, dividing people into specific groups is the beginning of a lot of misery, but unfortunately that’s the way our world (still) functions. It starts with our citizenship and ends with our religion or skin color, with all possible designations, stamps, and categorizations in between. If it was only a matter of naming, then of course nothing would be the matter, but these classifications and assignments do have annoying and sometimes also dramatic consequences for us and for others.

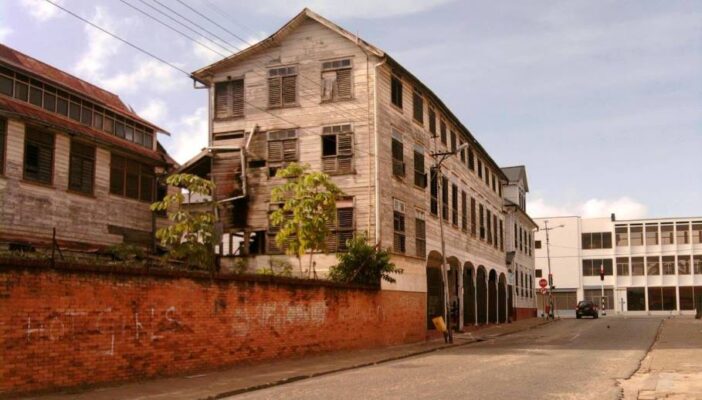

But before I really kick off with my discourse, I don’t think it would be a luxury to refresh your memory a bit. I think that’s important to obtain a better feeling of the matter, a better idea of what it’s actually about. Well then, in 1974 the population of Suriname was about 650,000 souls. In 2013, there are roughly 500,000 people living in the country. That is exceptional enough in an explosively growing world population. But how did this come about?

It all started in 1974, the year prior to Suriname’s independence. In a very short time, approximately 150,000 Surinamese left for the Netherlands — it was the first “great exodus.” There were concerns about the possible consequences of independence, especially because the so-called Separation Agreement (the “independence contract” between Suriname and the Netherlands, which is called the Toescheidingsovereenkomst in Dutch) stipulated that those who would reside in Suriname at the moment of independence would automatically receive Surinamese citizenship. However, anyone who was not in Suriname at hour “X” would keep the Dutch nationality. And although it was decided that a transition period of five years (1975 – 1980) would be applied to still be able to go to the Netherlands and become Dutch citizen, many packed their bags, just to be on the safe side.

The fearful premonitions became reality in 1980, when parts of the Surinamese armed forces seized power and eradicated the frail democracy. Thousands again left to the Netherlands, but also to the Netherlands Antilles and the United States, followed by an additional exodus after the infamous December Murders of 1982.

In the following years, people left sparsely (those who wanted to leave and had been able to manage that financially, had already left), but during the Civil War (Binnenlandse Oorlog) from 1986 to 1992, more than 30,000 people again fled (mainly East Surinamese Inland Creoles, the so-called Maroons), but this time mainly to French Guiana, which was done simply by crossing the Maroni river.

Today, the Surinamese diaspora (with descendants) in the Netherlands counts more than 340,000 souls, the one in French Guiana about 25,000, and the combined number of the United States, the Netherlands Antilles, and the rest of the world account for another 40,000 (apologies for any errata in numbers, but as studies contradict each other, it’s impossible for me to be accurate).

In any case, the final result of thirty-seven years of independence is as remarkable as it is moving: almost half of all Surinamese people do not live in Suriname. Furthermore, to this day, Suriname has to contend with an annual surplus of departures (particularly to the Netherlands). This is somewhat disguised by a growing influx of Haitians, Guyanese, and Brazilians, and a reasonable birth rate, which has kept the Surinamese population hovering around 500,000 for several years now.

Okay, now let’s start with the Surinamese legislation. In Article 18 of the Surinamese Immigration and Residency Regulations it’s written: “All who do not possess the status of Surinamese are foreigners.” If we apply this definition, it’s easy to determine if you are or are not Surinamese. So, for example, if you were born and/or raised in Suriname (whether or not from Surinamese parents), but you possess a nationality other than the Surinamese (even if you may have had the Surinamese nationality before), then, according to Surinamese law, you are not Surinamese. In fact, you are simply a “stranger.” Now, that might hurt a bit, but it certainly leaves nothing to be desired in terms of clarity.

How and when you officially become a Surinamese citizen according to Surinamese law is another (sometimes complicated) issue, in which country of birth, adoption, naturalization, descent, the Independence Separation Agreement (Toescheidingsovereenkomst), and the like are concerned, which is in itself quite fascinating, but for my argument not really relevant. Nevertheless, if you are interested in acquiring the Surinamese nationality, I would advise you to read the aforementioned Act for the Regulation of Surinamese Immigration and Residency (and I wish you a lot of fun while studying it). However, if you happen to be in the possession of a large and deep wallet, or if you come from China, for example, then worrying about this law is of course a completely unnecessary exercise; you will be Surinamese in a jiffy, without all the administrative hassle.

Yet, being or becoming a Surinamese citizen doesn’t automatically mean that one also feels Surinamese, or should feel Surinamese. Nonetheless, when we use colloquial speech and say that we are Surinamese, whether or not in possession of the Surinamese nationality, we usually mean that we also feel Surinamese, although we do not always explicitly state that. On the other hand, when people say that they feel Surinamese, the ultimate consequence seems to me to be that one also wants to adopt or at least tries to adopt Surinamese citizenship. I think you will agree with me that it’s ambiguous or at the very least peculiar if one claims to feel Surinamese, but in the meantime skips around with a different nationality than the Surinamese. I think that’s like having an amputated leg: you don’t have it, but it still itches.

Now, one can find my comparison misplaced and tasteless and dismiss things disapprovingly as just “a paper issue,” but then one could just as well opt for “the Surinamese paper,” I suppose. Because in that case one would really feel what a Surinamese person feels, for example, when they need a visa for France or for the Netherlands. Or, how exactly that “piece of paper” feels like when retirement age is reached, or when the children have to go study abroad. You see, then people usually prefer “the better piece of paper” — the practical piece of paper. In fact, the “what we feel” becomes “profiting from the best of both worlds,” and our principles, integrity, and solidarity are suddenly of much less importance.

But all that said, what exactly does it mean to feel Surinamese? Let me start by stating that this question will usually not occur to someone who actually feels Surinamese. Those are the kind of things that people “just feel,” without really needing to give explanations for it. I understand that, and this issue is therefore especially interesting for those who doubt their feelings. It therefore usually concerns members of the Surinamese diaspora or those who have returned to Suriname after a long(er) time to again try to live in Suriname.

Now, today there are African, Creole, Inland Creole (Maroons), Amerindian, Javanese, Hindustani, Chinese, Jewish, Lebanese, Antillean, Dutch, and also Haitian, Guyanese, and Brazilian Surinamese (my sincere apologies, if I have forgotten a group). In addition, a (gradually growing) group has emerged that belongs to the Surinamese “melting pot.” I realize I’m comparing apples with oranges here, because Judaism is a religion, for example, a Chinese is of the Mongoloid race and a Guyanese can be a Lebanese Christian, but I don’t want to complicate my story unnecessarily. What I want to point out is that those we call Surinamese come from everywhere and nowhere, so to speak, and can “be” anything and everything. Race, religion, cultural background or initial countries of origin have absolutely nothing to do with “feeling Surinamese.”

I also note that feeling Surinamese has not so much to do with feeling a connection to the Surinamese culture. After all, a homogeneous Surinamese culture hardly exists. Rather, there is a potpourri of competing cultures, and the nation is still far too small (in terms of population), too young (in terms of history), and too mixed (in terms of ethnic groups) for a dominant Surinamese culture. Moreover, the individual population groups — before and after their arrival in Suriname — each went through a history of their own. This includes those who experienced slavery and its abolition (period 1667–1863) and others who came to Suriname through labor migration (after 1863), or asylum migration (through the centuries).

Undoubtedly, everything will be different in five hundred or a thousand years, and surely a more general Surinamese (popular) history will be expounded, but for the time being the “Surinamese person” is little more than an invention. You could now point out that the Amerindians are indeed the “original Surinamese,” but it also applies to them that they were only relatively small groups, often also itinerant peoples who were unaware of national borders, and who didn’t know of any country called Suriname.

In short, what you look like, which God you believe in, and whatever one’s cultural and historical baggage may be, is not really relevant to feel Surinamese. But what does really matter then?

First, as commonplace as that may sound, there is of course “living together for a long time in a specific geographical area.” This, from generation to generation, living together or side by side of a group of people eventually forms its own dynamic, with special customs, norms, values, and laws, which translates into destiny, connectedness, togetherness, and solidarity. And thus, for the Surinamese situation it goes that those who are located within its geographical space and who “live their lives there,” are in essence “more Surinamese” and “feel Surinamese.” It’s a simple fact, and it’s the way in which (natural) nations and peoples are born.

If we then look at speech, we see that there are incessant discussions about which language or languages should be the official language of Suriname (with English, Portuguese, and Spanish as options due to Suriname’s geographical location), but the common, cross-cultural practice (and binding factor) is the use of Dutch and Sranan Tongo (Surinamese Creole language). Moreover, the close ties with the Netherlands (whether one likes it or not) and where about a third of all Surinamese live, will, especially as for the use of Dutch as a first language, be a fact that remains, and as such continue to exert a dominant, coercive influence.

A third factor is the step-by-step development of a common Surinamese history, however short that history may be, and however great the differences are between the various ethnic and cultural groups. Because with more than three hundred years of (mainly) Dutch colonization, the intermittent (forced and voluntary) migration waves, the independence of Suriname in 1975, the military coup in 1980, the December Murders of 1982, the Civil War between 1986 and 1992, and with the cautious and fragile restoration of democracy in recent years, there are foundations for a larger general history of Suriname and its people. Although these “milestones” had and have different consequences for individuals and for specific population groups, they undoubtedly also create a certain connection. We should also be aware that the real, own, self-determined Surinamese history basically only starts in 1975. If we take the latter into account, then Surinamese nation-building has only just transcended the embryonic stage.

Likewise, a Surinamese “national character” is gradually developing across different ethnicities, religions, and cultural backgrounds. This is of course a rough generalization, and often a caricature, but that’s always the case when it comes to a “national character.” The “Surinamese prototype” is in fact a mixture of both Asian and African elements of equanimity, courtesy, and pride, accompanied by imposed Dutch “civilization ideals,” postcolonial stress, and frustration, limited economic and cultural potential, and the influence of a demanding tropical climate. It’s necessarily a very general “spherical” impression, and there are, of course, always many individual differences.

Well then, the Suriname character can be described as follows: the Surinamese people are often late for appointments, have a Spanish mañana mentality, and often don’t keep their agreements and promises. The climate is partly to blame (a tropical climate makes people “slow”), but a strong anti-authoritarian nature also plays an important role, which is a reaction to former Dutch rule, and is expressed as: “I do as I want, whenever I want!” A Surinamese person always has big plans, but rarely executes them; they would really like to “go forward,” but they lack the experience, sometimes also the knowledge, but much more often the infrastructure (capital, manpower, internal market, organization, etc.) to get projects really going.

The Surinamese are also “bling-bling,” that is, people like to show (or pretend) that they have “made it,” which is expressed in fine and luxury material things, such as clothing, jewelry, the car(s), and the house, but just as often people boast of being of “good descent” or “having influential acquaintances.” Friends, family, and networks are essential, but that’s not surprising in a country in which arranging things through the official routes usually takes way too much time and hassle.

The Surinamese say they like “cultural activities” (because that’s chic), organize so-called “happenings” every now and again, but after all “culture” can’t really captivate the Suriname people, except then to be seen there, and to eat and drink plenty. In addition, everything that comes “from far” is actually better than what is from local produce.

Furthermore, a Surinamese person never says “No,” but only “Maybe” (which means “No”), and their “Yes” can be regarded as a “Maybe.” They like good (multicultural) food, music, dancing, parties, and family, they are hospitable, sociable, talkers, take the time, and like to “rest and relax.” They generally don’t like to talk about feelings, and they keep on smiling and being optimistic, even when there is nothing to smile or being optimistic about.

Partly recognizing oneself in the above (shared geographical space, language, common history and national character) is important, but not crucial to “feel Surinamese” though. What will be decisive, however, is whether you have truly come to love the country and its people. Whether you feel the country and its people “flowing in your veins,” whether you have built an “inseparable bond” there, and whether you still have strong family ties and friendships, including all the negative and positive feelings you may experience. If all that is the case, then you most likely also experience feelings of nostalgia, homesickness, melancholy, and alienation when you do not live in Suriname. These are feelings that are characteristic of a (young) diaspora. And the younger one has left the country (and/or the longer one has stayed away) and the older one returns (and/or the shorter one stays), the more people will doubt their own roots. Yet, as a whole, it is and remains an utterly personal matter, an individual “role play” that moves between “what was once” and “what is now.”

Nevertheless, it’s certainly not only your feeling that will be decisive, but also the feeling that Suriname gives you (for example, if you are there on holidays or if you return to settle there). And it’s precisely with the latter that the proverbial shoe “pinches,” and a lot of resentment, frustration, and — even more doubt arises. Because if you think that a “half-baked Surinamese” will be welcomed unreservedly and with open arms, you are wrong. And if you’re a Surinamese from the Netherlands (the big, bad ex-colonizer), which is usually the case, you will get your ass burned. In Suriname, you are generally regarded as someone who has “betrayed” the country, someone who left when it became or was “hot,” someone who has forfeited their rights to criticize the state of affairs in Suriname, an annoying, all too articulate know-it-all, who should better be humble and keep quiet.

Admittedly, some holidaymakers and returnees do pretend to be “king,” and unfortunately the entire diaspora is “punished” accordingly. Basically, it’s more favorable to be a “real stranger,” for example a Dutch Dutchman or French Frenchman, than the so-called “prodigal son.” In the Bible the latter is still warmly welcomed, but in Suriname he’s often mistrusted, tolerated at best, and perhaps accepted again after doing long “penance.” You understand that this will have quite an impact on your feeling of “being Surinamese.” This feeling therefore develops in a highly personal process, which is guided by a reciprocal dynamic — what or how you feel depends partly on what or how others feel about you, and vice versa.

Interestingly enough, Surinamese politicians often shout that all persons of Surinamese origin, wherever they are in the world, are regarded as Surinamese and are welcome to come to the country and help “to develop” it. I’m convinced that they are quite honest about this too, but the practice is often sadly different and a painful disillusionment. In addition, the rights of “Persons of Surinamese origin” are laid down in Surinamese legislation and in the Independence Agreement with Holland, but they are not fully respected.

Now, “Persons of Surinamese origin” are supposed to be treated as Surinamese at all times. This should mean, for example, that they do not need a visa for Suriname, that they can settle there without any problem, without having to possess the Surinamese nationality, or first having to become “Surinamese Resident” which involves piles of paperwork. Unfortunately, Suriname does not enforces its own legislation and promises, in any case, they are not (consistently) applied. Some have therefore tried to take the Surinamese state to the (international) court with regard to this matter, but so far, without much success.

To be fair, I must add that for some things it’s indeed easier to be of “Surinamese origin” than a “real stranger.” For example, a (longer-valid) visa is easier to obtain. This also applies to a residence permit, but you will nevertheless be plagued with unnecessary administrative (and financial) formalities and you will also have to demonstrate that you have regular and sufficient income (including a registered roof over your head). You may find the latter “just logical,” but bear in mind that a Surinamese citizen does not have this obligation (he may be as poor as Job). And finally, this is about the promise that Persons of Surinamese origin would be “treated as Surinamese at all times.”

It’s sometimes said that “time heals all wounds,” and in a sense, of course, there is an almost frightening truth in that. Because behold, the ex-dictator is now friends with his biggest rival (the former guerrilla leader), and they happily rule the country together. A military officer, who has come to power unlawfully, eventually becomes lawfully president. Those who never wanted to return to Suriname have returned, and those who once did, have left and don’t think about it no more. Things change, the sharp pain often levels off, is sometimes tucked away or forgotten, and compromises are made. Suddenly things are gray, and no longer black and white. It’s one of those absurd, paradoxical things in life, and sometimes you really can’t make heads or tails of it anymore.

Well, I hope I haven’t added to your confusion. My advice on this matter is: if you’re a doubter and want to gain certainty (and have the financial and social resources to do so), there’s really only one thing you can do and that’s — go back! Live there. Work there. Feel there. And accept that it won’t be easy.

Personally, I haven’t done all that (yet). I’ve only stuck out my “feelers” a few times, and today I’m not sure I want to still try. In the past thirty years, Suriname and I have changed, and I have a hard time with the differences that have grown over time. Returning would mean that I would have to “reinvent” both myself and Suriname, and frankly, I’m not sure if I can. I don’t think I have the energy for Suriname, as I don’t have it for Holland any longer. I think I now prefer to be a real stranger somewhere else, in a “neutral” country.

However, I have not completely given up hope, and I do appeal to the Surinamese government and the Surinamese population to fully and unreservedly open the doors for the Surinamese diaspora. Not everyone can or wants to come back, but I am convinced that tens of thousands will. Not only to enjoy their Dutch pension, but also to actually make an active contribution to the further development of Suriname, and make Suriname and themselves a success story. Many, including me, have only been waiting for the sincere and wholehearted “Yes” word. Waiting on a “in good and in bad times,” on a “in sickness and in health,” on coming home and being at home, on “feeling Surinamese,” and also of being allowed to be Surinamese again.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.

Find themed health, wellness, and adventure holidays around the world.